Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The first time I watched The Secret of NIMH, if my memory serves, was in the break room at La Petite France, in the northern suburbs of Cincinnati, where I’d been stowed while waiting for my mother’s waitressing shift to end. The climactic swordfight, which I watched several more times through the course of my childhood, I would remember as the most brutal thing that I had ever seen.

In actual fact there are only a couple dabs of blood visible in this scene, a fact I noted with surprise the first time I watched The Secret of NIMH as an adult. This was in the mid-aughts, in some annex room at Symphony Space with folding chairs set up for a kiddies’ screening, though I was myself on a date (it made sense at the time, in a kind of inside joke-y way). NIMH (1982) is the directorial debut of Don Bluth, who’d formed his Don Bluth Productions with a gang of defectors from The Walt Disney Company. Through the ‘80s, Bluth Productions was a viable competitor for The House that Walt Built, and NIMH, based on a children’s book by Robert C. O’Brien, shows a good hand with subterranean atmosphere, its detail work certainly exceeding anything to be found in contemporary trace-along Disney works like The Rescuers and The Fox and the Hound. What really stayed with me after re-watching, though, were the touching and tremulous line readings of the actress voicing Mrs. Brisby, the widow of heroic Jonathan Brisby, a brown field mouse left alone to care for her children. One moment is particularly rending: Mrs. Brisby is hidden behind tall grass, and we cannot see her, but we hear her say in a private voice that is very close to a sob: “I wish Jonathan were here.”

Image may be NSFW.

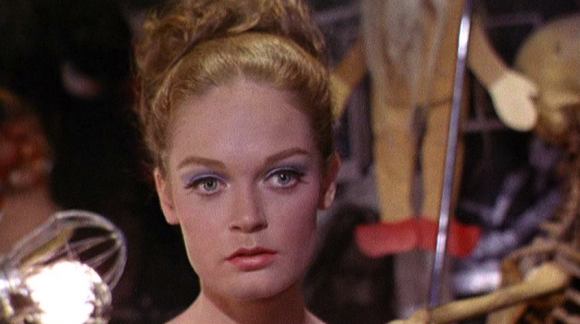

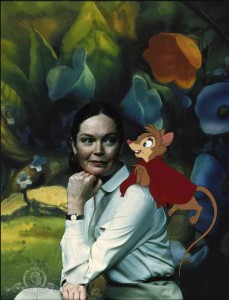

Clik here to view. Mrs. Brisby’s voice belonged to Elizabeth Hartman, an actor who I knew by then from Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971). Now, there is a great deal that goes into a screen performance, but I cannot escape the impression that voice is in many respects an actor’s quintessence—when James Gandolfini died last week, many who were looking to encapsulate the sum total of the loss turned to Gandolfini’s performance in Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are, a film in which the actor never appears in the flesh, yet a role which epitomized Gandolfini’s combination of looming bulk and disarming vulnerability. A number of great actors, usually prompted by the failing of their bodies, have given their final performances from the recording booth—Paul Newman, Orson Welles, James Stewart—for the famous voice is the last to go. And as it happens, Secret of NIMH was Elizabeth Hartman’s final performance, though she wasn’t even forty when she read her part—but more on that in time.

Mrs. Brisby’s voice belonged to Elizabeth Hartman, an actor who I knew by then from Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971). Now, there is a great deal that goes into a screen performance, but I cannot escape the impression that voice is in many respects an actor’s quintessence—when James Gandolfini died last week, many who were looking to encapsulate the sum total of the loss turned to Gandolfini’s performance in Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are, a film in which the actor never appears in the flesh, yet a role which epitomized Gandolfini’s combination of looming bulk and disarming vulnerability. A number of great actors, usually prompted by the failing of their bodies, have given their final performances from the recording booth—Paul Newman, Orson Welles, James Stewart—for the famous voice is the last to go. And as it happens, Secret of NIMH was Elizabeth Hartman’s final performance, though she wasn’t even forty when she read her part—but more on that in time.

Elizabeth Hartman was raised in Boardman, Ohio, a suburb of Youngstown. She was the middle child of three, born in comfortable circumstances to William and Claire Hartman, a building contractor and housewife. All accounts seem to agree that Elizabeth, nicknamed “Biff,” was desperately shy from an early age, though she was pretty—she modeled for a Brooks Brothers’ store in Cleveland—and able to slough off her shyness completely when walking the boards. Hartman began painting scenery and working as an usherette in the Youngstown Playhouse as a teenager, later appearing there in “A Clearing in the Woods,” which first gave her a firm idea of her vocation, an ambition that was solidified when she won Ohio High School Actress of the Year for her role as Emily Webb in the Boardman High School production of Our Town. Thornton Wilder’s play is a work almost cruel in its pathos—seeing the David Cromer-directed production at the Barrow Street Theatre in 2009, I felt a horrible lump in my throat from the moment the stage manager began to address the audience and describe the dimensions of Grover’s Corners, for I knew that if this play was done right I would be a blubbering catastrophe by the third act, and it looked very likely that, yes, it was going to be done right. Just to think of Emily’s “My, isn’t the moon terrible?” delivered in Ms. Hartman’s voice, with its particular little catch, is almost too much to endure.

From Youngstown, Hartman went to study acting at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon) in Pittsburgh, where she met her future husband, Gill Dennis, then working as a stage director. Her classroom experience was supplemented by work with the Kenley Players in Warren, Ohio, whose director, John Kenley, would remember her as “very pretty in a Victorian way,” which is spot-on. Hartman had a face designed for a cameo, long strawberry blonde hair meant to be woven into jewelry or pressed between the pages of a book as a forget-me-not keepsake.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Hartman left Pittsburgh to make a go at New York, passing a summer at the Barbizon Hotel for Women, but she failed to set Broadway ablaze. Finally returning to Kenley, Hartman was put in touch with agent Howard Rubin, who in turn brought her to the attention of MGM—and the very same Little Nell quality that Kenley had noted came through in her screen test for A Patch of Blue. Adapted from Scotch-Australian-Japanese novelist Elizabeth Kata’s Be Ready with Bells and Drums, A Patch of Blue depicts the friendship between Gordon, a black newspaperman, and Selina, a poor blind white teenager who is ignorant of her friend’s color, but blissful at his attentions. English director Guy Green—coincidentally the cinematographer on both of David Lean’s Dickens films—also wrote the screenplay for Patch, transposing the scene from the Deep South to downtown Los Angeles, to the benefit of the film’s credibility.

Hartman left Pittsburgh to make a go at New York, passing a summer at the Barbizon Hotel for Women, but she failed to set Broadway ablaze. Finally returning to Kenley, Hartman was put in touch with agent Howard Rubin, who in turn brought her to the attention of MGM—and the very same Little Nell quality that Kenley had noted came through in her screen test for A Patch of Blue. Adapted from Scotch-Australian-Japanese novelist Elizabeth Kata’s Be Ready with Bells and Drums, A Patch of Blue depicts the friendship between Gordon, a black newspaperman, and Selina, a poor blind white teenager who is ignorant of her friend’s color, but blissful at his attentions. English director Guy Green—coincidentally the cinematographer on both of David Lean’s Dickens films—also wrote the screenplay for Patch, transposing the scene from the Deep South to downtown Los Angeles, to the benefit of the film’s credibility.

The first shot in A Patch of Blue is a pair of shaky hands—Hartman’s—stringing beads. Her Selina is a blind girl reduced to Cinderella servitude, her existence confined to the four soiled walls of the apartment where she’s imprisoned doing house and piecework for her family: her drunk, desiccant grandfather (Wallace Ford) and her slovenly, waddling tyrant of a mother (Shelley Winters, setting the bar for Awful Tenement Mother of the Year, only to be outdone in gorgon monstrousness by Mo’Nique in Precious.)

After a great deal of begging, Selina convinces her grandfather to deposit her in a neighborhood park for the day, and there she meets Gordon, played by Sidney Poitier at his most human and humane. Gordon brings Selina little things—pineapple juice, a pair of sunglasses—which, in her meager life, take on the aspect of wonders, exotic gifts from a faraway world. He even brings her back to his apartment, where Ivan Dixon, then recently the star of Michael Roemer’s Nothing But a Man, shows up as Gordon’s dubious brother. He has some right to doubt Gordon’s motives: No mere racial goodwill play acted by eunuch cyphers, A Patch of Blue deals with a flesh-and-blood couple, and Gordon’s saintly altruism is brought down to earth by ethically dicey lust, for though Selina is essentially a trusting, naïve child, she has a woman’s body and desires. (Two years before Loving vs. Virginia, A Patch of Blue contains one of the first interracial kisses in American movies, between a chalk-pale white girl and a ebony black man, and there is nothing chaste about it.)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Green lays on the lurid flashbacks rather thick but, with Hartman’s help, he does remarkably well conveying sightless, untutored Selina’s subjective experience of the hazards of negotiating a simple city street. Patch of Blue can be fairly called Dickensian, and Hartman suits this because she has the ability, through her absolute unselfconscious emotional transparency, to make goodness—bright, ecstatic, incandescent goodness—seem really appealing, which was among Dickens’ particular gifts. As much as her joy, Selina’s terror comes through undiminished by the filters of actorly decision-making—witness her distressing abandonment in the park during a flash thunderstorm. Writing about Hartman, critics almost always have recourse to the same words: haunted, vulnerable, fragile, delicate. Speaking of her work in Walking Tall, Pauline Kael pinpointed Hartman’s appeal thusly: “You want to reach out to her.” And that is here from the beginning: Hartman’s Selina is like some breakable thing perched on a threatening precipice, and you feel compelled to protect her, secure her in place.

A Patch of Blue is released. Hartman is nominated for the Best Actress Academy Award and Golden Globe. In Youngstown, April 18th is declared Elizabeth Hartman Day. Yet on the cover of the 2003 Warner DVD release, only Winters and Poitier’s names are deemed marketable enough to appear about the title. What took the shine off such a promising debut?

Hartman’s next film, Sidney Lumet’s The Group, was a two-and-a-half-hour, two-and-a-half million dollar epic drawn from Mary McCarthy’s 1963 bestseller of the same name. A bona-fide moneymaker, it would seem a solid sophomore outing, but it was also a messy ensemble film where loose pieces tended to get lost in the shuffle. The Group follows a clique of eight Vassar friends from their 1933 graduation—at the dawn of the Roosevelt presidency and into the midst of the Great Depression—to the beginning of World War II. Their stories are bookended by two ceremonies at St. Mark’s Church: The wedding of Joanna Pettet’s Kay to a would-be playwright (Larry Hagman), and Kay’s funeral, after her marriage has gone bust and she’s tumbled out of her hotel room window while listening to the news of Hitler’s tanks rolling into France. Hartman apparently turned down meatier roles to play Priss, a worrywart Economics major who goes to work for the NRA, only to ultimately find herself under the heel of her tyrannical pediatrician husband.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

While wearing its social import on its sleeve, The Group is basically a slapdash piece of work, hampered by an insensibility to the period it portrays, a visual murkiness that’s surprising considering that Boris Kaufman is cinematographer, and thudding conceits like the repeated ironic use of a school song chorale. All of these faults and more were dutifully chronicled by Kael, on-location taking notes for what would become her 25,000-word “The Making of The Group,” which was commissioned and turned down by Life magazine. In its stead, Life published Kael’s short profiles of The Group’s actresses under the title “A Goddess Upstages the Girls” (“The Goddess” in question being the effortlessly supreme Candace Bergen.) Kael’s comment on Hartman, later much quoted: “Whether she can develop the toughness necessary for a real acting career is the only doubt one might feel for her future.”

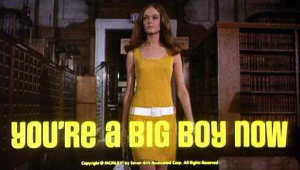

Throughout her roasting of the impersonal professionalism of the present generation of TV-to-movie directors, which Lumet’s shortcomings were taken to be indicative of, Kael seemed to be urging an American New Wave into being through sheer force of will. Hartman’s next film, 26-year-old Francis Ford Coppola’s sex comedy You’re a Big Boy Now (1966), adapted from a novel by David Benedictus, showed something of the same ambition. Though the on-the-fly street photography of contemporary New York–inspired by the Nouvelle Vague‘s freewheeling use of Paris–gives Big Boy a certain documentary appeal today, the insistently innovative technique belaboring what is essentially a burlesqued bildungsroman, all edited into a madcap fluster by Aram Avakian, adds up to a case of the strained zaniness that typifies counterculture comedy.

More than for views of since-demolished Luncheonettes and an under-construction Madison Square Garden, though, Big Boy is worth seeking out because it showcases a rare example of faith in Hartman’s range, showing her for a great deal more than an off-brand Sandy Dennis. Hartman is one of those mutable actors who can be exactly as attractive as they need to be in the moment—in A Patch of Blue she appears rather homely at first, with a blunt expanse of forehead, wincing smile, and a turned-in slouch, but as soon as Gordon starts to call her beautiful, beautiful she becomes.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. In The Group, Hartman’s Priss is the most meek and mild of the bunch, mocked as “so flat down there she’s never had to wear a brassiere,” mortified by her body and not least her inability to breastfeed. And yet here, the same year, in the opening tracking shot of Big Boy, is the very same actress with the very same body, indomitably strutting the floor of the New York Public Library reading room like it’s a runway to the strains of The Lovin’ Spoonful. (Coppola did his part to build his starlet’s confidence, taking her on motorcycle rides where he would roar above the sound of the engine: “You’re sexy, beautiful, Barbara Darling!”)

In The Group, Hartman’s Priss is the most meek and mild of the bunch, mocked as “so flat down there she’s never had to wear a brassiere,” mortified by her body and not least her inability to breastfeed. And yet here, the same year, in the opening tracking shot of Big Boy, is the very same actress with the very same body, indomitably strutting the floor of the New York Public Library reading room like it’s a runway to the strains of The Lovin’ Spoonful. (Coppola did his part to build his starlet’s confidence, taking her on motorcycle rides where he would roar above the sound of the engine: “You’re sexy, beautiful, Barbara Darling!”)

Barbara Darling is an inscrutable Off-Off Broadway ice queen who moonlights as a go-go dancer—or is it the other way around? (The name may be a nod to Darling, the film that provided Julie Christie the chance to make off with Hartman’s Patch Oscar.) Big Boy’s nominal protagonist, Bernard, a put-upon gap-toothed virgin played by the Canadian actor Peter Kastner, is ensorcelled by Barbara at a performance of a caricatured avant-garde piece called The Department Store in which she appears in the mute role of a mannequin, looking dispassionate as a Grecian marble beneath piled red hair. A smitten Coppola gives Hartman a few such iconic moments, filming her poised atop the Alice in Wonderland statue in Central Park, or jerking her torso wildly above the dance floor of a nightclub where, improbably, scenes from Coppola’s Dementia 13 are being projected onto the walls.

It’s a siren’s frug, a dance of death! In pursuing and “catching” Barbara, Bernard is unwittingly reduced to her doormat, a live-in lover unable to even enjoy consummation because his beloved has the cock-withering habit of taking on a maternal demeanor in intimate situations and airily referring to herself in the third-person. All of this is but a game for Barbara because, as established in a blithe flashback skit, she’s had it out for men in general ever since being molested in boarding school. (If taking such a matter lightly seems crude, it can only be said in defense that the film takes everything lightly.) Hartman, younger even than her would-be wunderkind director, nevertheless brings nuanced insight to a role which, on the page, is little more than that of a castrating bitch. If Barbara keeps herself scrupulously in control, Hartman makes it evident that Barbara is herself not in control of the forces that demand control of her. Barbara Darling is, in short, a bit of a schizophrenic, most piteous when she’s at her most pitiless—as Hartman’s quavering voice rises to become something jagged, strident, serrated, you somehow feel concern for the monster, not the prey.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

As a comedy, You’re a Big Boy Now is a flop in every respect, but Barbara Darling works on her own wavelength. Hartman finds a profound connection with a trite character, perhaps because there is something of Hartman in Barbara, both inveterate escapists: We are told that boarding school Barbara was “Unhappy every day… except when they show the movies,” while John Kenley said of his protégé that “She was a finished actress when she got on that stage. She disappeared into the woodwork when she got off.”

A period in the woodwork was coming up. You’re a Big Boy Now was followed by strictly routine work in John Frankenheimer’s The Fixer (1968), which was in turn followed by inactivity as Hartman, uniformly disappointed by forthcoming offers, walled up in her E 68th St. apartment to re-read Emily Dickinson. Talking to the NY Times’ Judy Klemesrud for a 1969 article titled ‘After A Patch of Blue, Gray Skies,’ from which the preceding motorcycle anecdote comes, Hartman described this period as “my slow, quiet breakdown.” Klemesrud caught up with Hartman in December, 1969, shortly after her marriage to Dennis and her Broadway debut, in which she appeared with Henry Fonda, Ed Begley, and Margaret Hamilton in none other than Our Town—a Plumstead L.I. Playhouse production presented at the ANTA Theatre, today the August Wilson. (Hartman had been offered the part of Emily by Martha Scott, who originated the role.)

While waving off rumors of her extreme introversion as an embellishment of the MGM publicity department with one breath, Hartman confirmed them with the next: “The real me, I guess, is the shy, up-against-the-wall person. I like sympathy. I like people to feel sorry for me… You can tell from your fans what you are, I’ve got the adolescent crowd and the poetic boys. Those are the kinds of people who write to me and stop me on the street. It’s certainly not the lusty men.” But in her next role, Biff, Elizabeth and Barbara Darling would be tested against heretofore unseen levels of machismo.

PART 2 NEXT WEEK, BOMBASTKATEERS!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.